Below are tables comparing the expectations for Levittown upon its conception and what reality was actually like for residents once the town was built. Our examples are in reference to David Kushner’s book Levittown: Two Families, One Tycoon, and the Fight for Civil Rights in America’s Legendary Suburb.

Reimagining Levittown: A Site of Racial Conflict and Resistance

Expectations: |

Reality: |

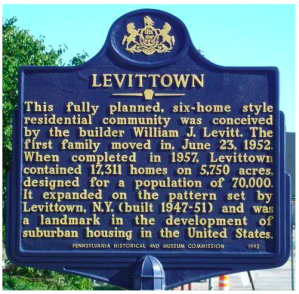

Planned HomogeneityWilliam and Alfred Levitt, Levittown’s designers, builders, and owners, wanted to keep this new development pristine and pure: “white.” They claimed that an influx of any color, especially blacks, would drop the property values; they did not want to jeopardize their profits.The Levitt brothers were able to keep Levittown’s entire 6.9 square mile radius free from blacks and lower class families for the first six years of its existence, successfully isolating the suburb from the realities of post WWII America (61). |

Miscalculated Means and MotivesIn the beginning, Levittown was legally permitted to exclude non-caucasian individuals from buying homes. But in 1948, the Supreme Court ruled discrimination by race unconstitutional and logistically problematic (Kushner 43). Blacks were allowed by law to buy property in Levittown, yet, the Levitt brothers continually escaped prosecution (68).

|

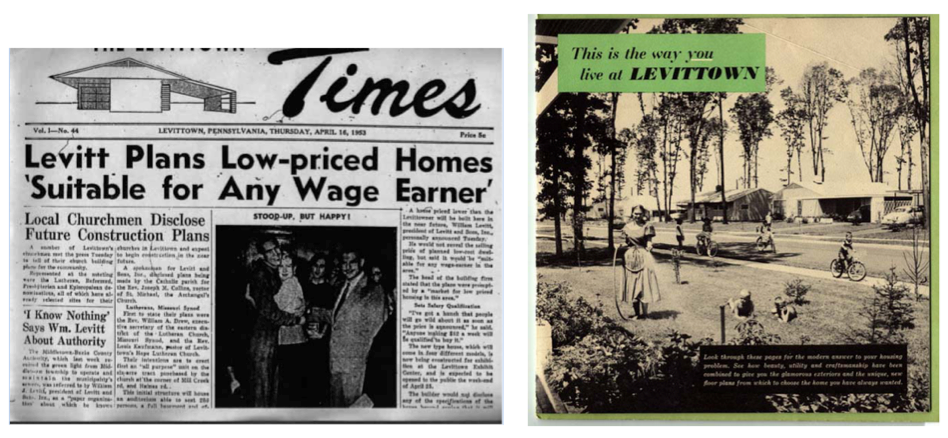

This newspaper article below on the left advertises Levittown as a place for the average American wage earner. However, it fails to disclose that only a limited pool of people actually qualifies as the average “American.” People of color, as the Myers learned, were not welcomed as Americans deserving of a home in Levittown. The photo on the right displays the ideal life for women in Levittown. As is shown, a woman partakes in work around the home as she is surrounded by many children. This emphasizes her role as the homemaker, nurturer and mother. It should be noted that there are absolutely no people of color shown in this advertisement.

Perfection as Protection from Changes and CommunismAs sixteen million veterans flooded back into the United States, securing a home meant restoring an American way of life. At the close of WWII, houses were much more than homes. Americans believed that “home ownership was an explicit way… to keep the nation strong” against communism (28). Those who protested against Levitt’s housing discrimination faced similar treatment to those emotionally affected by Emmett Till’s death: they were deemed communists (44, 53).Levittown was supposed to be sublime. The houses, each equipped with the latest technological fashions, looked identical. The mind-numbing order of the neighborhood attracted veterans who were looking for a normalcy that had ceased to exist after World War II. In fact, Levittown reinforced pre-war nuclear gender roles, encouraging men to be the masculine bread-bearer and women to be the respectable mother and housewife.Everything in Levittown was set in perfect order; even the yards were pristine. Abe Levitt, the father of Levittown’s creators, used to patrol the neighborhoods, swooping in to complete unfinished yard work. After making sure each lawn was indistinguishable from the next, he’d leave a bill on the doorstep. Everything, right down to the very tips of grass, was meant to radiate flawlessness. |

Internally Broken and CorruptWhile rape, drugs, and hate were present in the real world, Levittown residents considered themselves removed from the evils of humanity and societal problems. But, Levittown residents were far from perfect.In 1954, a young veteran raped and killed a fifteen-year-old girl (73). The world was shocked that such an event could occur in the haven that was Levittown.

|

Below is a video that highlights Levittown as the ideal place for middle class Americans to live. Similar to the popular narrative that surrounds suburbia in the United States, the video emphasizes the normalcy of Levittown’s residents and their tight-knit community. Nothing is mentioned about the racial segregation and extreme physical and psychological violence that erupted after Levittown was built, enabled by the government’s decision to turn a blind eye to its exclusive and racist housing policies.

A Place for PeaceAmerica was supposed to be a land of opportunity. The Quakers founded Pennsylvania as a shelter for those oppressed and in danger (104). Suburbs were made for families. Levittown was intended to be inhabited by the best American citizens. And after one of the most gruesome wars in history, the public wanted to keep violence behind closed doors.Bill and Daisy Myers didn’t move to Levittown to instigate an uproar. They were ordinary people, hoping for an affordable home, equipped with a garage just large enough to accommodate their growing children. |

Terrible TurbulenceAlthough Bill and Daisy entered Levittown with the same intentions as their white neighbors, they questioned whether or not they could “live a normal, happy life” there even before they moved in (83). Is questioning one’s safety a common characteristic of the picturesque American suburb? Yes, if you’re black.When the Myers family entered Levittown, violence broke out and hate penetrated the community. Mobs gathered with their confederate flags outside the Myers’ home, trashing their yard, pelting rocks through their windows, filling their mailbox with threats, and leaving terrifying phone calls. Crosses were burned outside and the letters KKK were painted on their home, branding Levittown as a neighborhood of intolerance (175).Leaders of the mob insisted that they didn’t encourage violence, yet they did nothing to stop it (114). Daisy and Bill, fearful for their lives, found comfort in the fact that if they were to be murdered, their baby would be “too young to know” (120).

|

Levittown stands as another one of America’s successful endeavors in pitting people of color against one another. If Levittown had taken place only a few years earlier, the Levitt brothers would have been considered Jewish, not white. Yet, the acceptance of their whiteness and the United States’ ability to erase the Levitt’s colored status demonstrates that race is both performed by the individual and subject to external societal changes. Additionally, American society divided the lower class. Eldred Williams, the main perpetrator of the mob’s violence, was an unemployed white man(138). He felt outraged that a black family could have something he lacked, because American culture had always assured him of his absolute, unchallenged superiority over other races. He used white supremacy to mask the shame he felt towards his own class status.

When Daisy Myers encountered the leaders of the hate mob, who had continuously violated her rights both as an American citizen and a human being, she found them to be much smaller than she imagined. She described them as “trapped mice seeking the nearest hole in which to hide” (172). This reveals that even though the mob’s voice was loud and the hate was large, the people were driven simply by class fear and racial anxieties. viol

The court case eventually ended with the declaration that nothing can legally be done to “keep Negroes out of Levittown,” for there is no “legal way” of segregating Levittown “under the sun” (179-180). But, is this enough? During the mob’s final days, cries and chants of “this is America” filled the air of Levittown, Pennsylvania, and these words won’t truly leave until this neighborhood’s inhumane history is openly acknowledged and widely known (115).