World War II and the Beginning of Suburbia

After WWII, returning veterans created a demand for housing that exceeded the number of homes available. These young and quickly growing families needed more space than city apartments could provide. Seeing an opportunity for profit and to serve American veterans, the Levitt brothers set out to create a “dream community,” fostering post-war American values. Similar developments were built on outskirts of other cities as well to meet housing demand and enable more families to access the American Dream.

The Housing Bill was created as part of the GI Bill in 1948 to allow returning veterans to afford new houses. Houses were often too expensive for young veterans, so The Housing Bill created an opportunity for veterans to get long-term, low interest housing loans. These could be repaid over decades with only a small down payment, making house buying a reality for the “average” American for the first time.

Inequality in the GI Bill

The Housing Bill was created as part of the GI Bill in 1948 to allow returning veterans to afford new houses. Houses were often too expensive for young veterans, so the Housing Bill created an opportunity for veterans to get long-term, low interest housing loans. These could be repaid over decades with only a small down payment, making house buying a reality for the “average” American for the first time.

However, the “American Dream” was denied to many minorities, particularly black Americans, through systematic discrimination at various stages of the housing process. At the preliminary level, veterans who were dishonorably discharged were denied access to the benefits of the GI Bill. It is important to note that black veterans were dishonorably discharged at a highly disproportionate rate, greatly hindering their access to the opportunities afforded by the GI Bill. Bill Levitt openly stated in clause 25 of the neighborhood lease that Levittown would not allow black residents. Additionally, it was nearly impossible for black veterans to get approved for loans, and when they did, it was often at the hands of predatory lenders, which led to a series of foreclosures in years to come. In fact, the loans that were provided by the Housing Bill specifically for veterans were not given to black veterans. Regardless of whether African American families were able to obtain loans to buy a house, neighborhoods were purposefully segregated. Realtors would strategically not show black families homes in white neighborhoods. They were only shown houses in poor, black neighborhoods, reserving “desirable” houses for whites, even if these homes were affordable for the black family. In terms of longitudinal effects, the series of foreclosures following loans from predatory lenders greatly halted the growth of generational wealth within African American communities.

Legal Racism and its Consequent Legacy

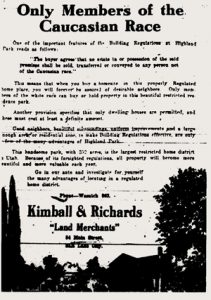

Levittown and similar housing developments had written policies to exclude minorities from the community. Rental leases and homeowner contracts explicitly stated that people who were “not members of the caucasian race” were prohibited from renting or owning in Levittown.

Around the mid-20th century, there was a wave of communism due to the desire of civic conformity. McCarthyism was a more favorable political campaign in the U.S. Therefore, in addition to racial segregation, the Levittown housing policy strictly prohibited communists from owning property in Levittown.

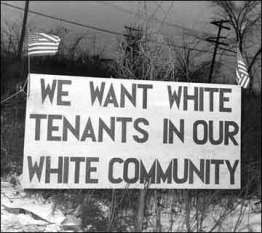

“Redlining” was another political strategy used to ensure segregation of neighborhoods. Redlining is the cycle by which banks, loan providers, and lawmakers use policy to intentionally create segregated neighborhoods. Realtors and homeowners often steered black families away from white neighborhoods, fearing the decrease of home values. The suggestion that integration would devalue homes allowed realtors and constructors to justify refusing to sell to non-whites, but this phenomenon was not necessarily true. Some white people stated that as long as the neighborhood was nice, they would be satisfied living next to a black family. Moreover, statistics show that the homes in several integrated towns did not decrease in value. But this suggestion created a surplus of vacant houses and lowered home values where black families lived, and as long as the myth continued, Bill Levitt refused to sell to any non-white families. The resulting other neighborhoods with more people of color were redlined, and because of this were denied funding and services that white neighborhoods easily obtained. These forms of housing discrimination remained legal until the 1968 Fair Housing Act, but continued in practice well after its passage.

In 1957, the Myers family was the first black family to dismantle Levittown’s homogeneity. Since the Myers bought their house from the previous owner rather than through Levitt himself or a real estate agent, they were able to avoid Levitt’s anti-black policies. The Myers’, however, were met with continuous mob violence and death threats. The white members of Levittown threw rocks through their windows and burned crosses on their lawn. The KKK came to Levittown to help force the Myers out. Nonetheless, the family remained persistent in their right to live where they pleased. They pressed criminal charges against members of the mob, and the court appropriately persecuted those that threatened the family, sending a message to the residents of Levittown that racism would no longer be tolerated.

Despite events such as the Myers’ victory in court and the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 that criminalized racist housing policies, the legacy of segregation largely remains in suburbs, as evidenced by the fact that today, only 3.3% of Levittown’s population is black. Although discriminatory policies have since been lifted, segregation has remained a truth in American suburbs. Today, cities and suburbs are still deeply segregated, and practices such as redlining have deeply entrenched segregation into American housing. Black families still are far behind white families in terms of home ownership, and in 2016, the National Fair Housing Alliance received over 28,000 reports of housing discrimination. While Levittown may be a relic of the past, the practices that perpetrated its segregation still linger today.

How Policy Influenced the Myers’ Family Decision

Public Housing in NY is reminiscent of institutions such as jail. This housing was typically occupied and marketed to black families in the rise of suburbs such as Levittown. One can infer that one is inferior to the other, especially in respect to the “American Dream.”

Levittown was marketed as a modern, high quality housing option with manicured lawns and brand new appliances. It was a luxury neighborhood with schools, grocery stores, and swimming pools available to all community members. Levittown exemplified the American Dream within a community of close friends. There was only one caveat: it was for whites only.

In a documentary created during the Levittown crisis, residents of Levittown were interviewed and asked about how they felt about the Myers family moving into Levittown. One of the most common responses was “I don’t know why they would want to move here” or concerns about how life here would be hard for their kids. One thing the white suburban residents of Levittown failed to consider is what their other options looked like. Although the famous FDR New Deal invested more in public and affordable housing for the poor in the United States, the public housing was segregated under the neighborhood composition rule that hoped to bring the “segregated character” of neighborhood to public housing.

With segregated public housing, more money was poured into white public housing than public housing for minorities. The living conditions were much better and they had more amenities. Even if there were vacancies in the white public housing, minorities were not allowed to move in. The Myers family would have been subject to poorly funded public housing, which also contributes to the funding and quality of local school districts. While the date of the New Deal was almost two decades before the Myers decided to move to Levittown the effects were still being felt. In 1949 legislators passed the Housing Act of 1949 as a part of the Fair Deal proposed by President Harry Truman. This deal had the intentions of increasing the quality of life in public housing; however, a lot of people criticize it for not actually increasing the quality of housing for the poor but rather creating options that did not accommodate to the current inhabitants, most of which were minorities. On top of the poor execution of the housing bill, an effort to defund public housing and ruin the bill was made conservative lawmakers. They proposed an amendment to the bill known as the “poison pill”, which proposed integrating public housing on the hopes that lawmakers would no longer support the housing bill.

Even after the Housing Act of 1949, the quality of public housing for blacks and minorities did not change much. White America was flooding to the suburbs and leaving everything behind. The hopes for a better life, to live the true American dream in a district with better education for their kids, and to have a house of their own might have been some of the motivating factors for the Myers moving to Levittown. It was not until the 1968 Fair Housing Act that discrimination for housing was legally discontinued, although there were still ways around it.